The Language Of The Hopeful

The constructed language Esperanto was invented over 130 years ago. In Austria and elsewhere there are still “Esperantists” who learn and speak the language. I visited a study group in Vienna.

A hundred years ago, the inventor of Esperanto, Ludwik Zamenhof, died. The constructed language itself celebrates its 130th birthday this year. In Austria and elsewhere there are still “Esperantists” who learn and speak the language. I visited a study group in Vienna.

A bookshop in the second district of Vienna. Despite the shop being closed, there is a lively hustle and bustle in the salesroom. The sign at the entrance door reveals why: Closed Society – Esperanto Rondo.

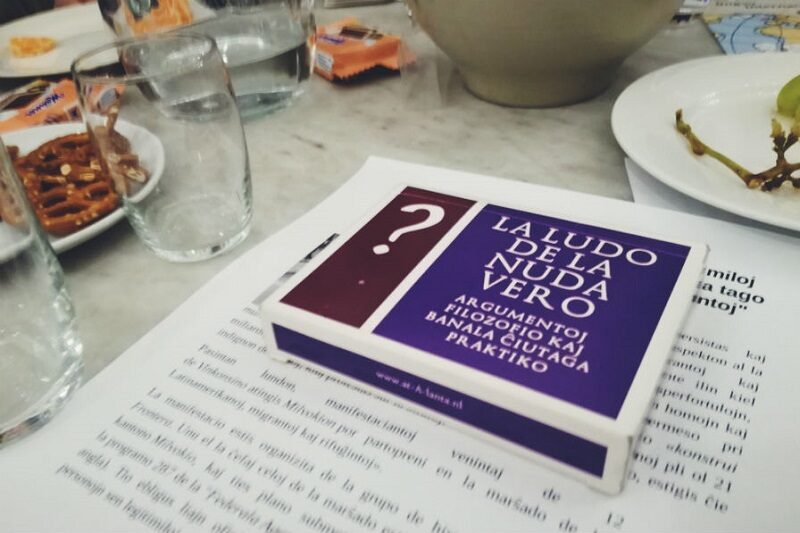

The Esperanto Rondo is a study group that meets every fortnight to learn Esperanto, the most widely used constructed language – or conlang – in the world. Students read and translate texts, and questions about grammar and vocabulary are answered. As a side dish, wafers, pretzels and whippet cookies are served.

Courtesy by Uwe Stecher

The youngest participant is Daniel. Born in Russia, he is in his final year of grammar school. Besides Russian, German and Esperanto he speaks Ukrainian, English and French. Less than three months ago he started learning Esperanto with a smartphone app. He translates today’s exercise text with ease.

Speakers from all levels are present: there’s a university student; a young woman who grew up bilingually with German and Croatian; a French expat who works in Vienna; and a guest from Slovakia who is an active Esperantist in Bratislava. And four people who are practically fluent in Esperanto.

The Esperantist Round has finished translating the exercise text – and after work, there comes play: “La Ludo de la nuda vero” – the game of naked truth. Each participant takes turns drawing a question card, reads it out loud and needs to answer it in Esperanto. Either just with “Jes” or “Ne”, or in more detail.

“Ĉu vi indulgas homojn kiu ne toleras kritikon?” asks Mateja. Whether she indulges people who cannot stand criticism. “Ne”, she replies very firmly – the group laughs. No discussion on this question.

Two Anniversaries In One Year

This year marks the hundredth anniversary of the death of Esperanto “inventor” Ludwik Zamenhof. 130 years ago, the Polish ophthalmologist laid the foundation for the language. His 16 rules are still valid today. Zamenhof’s vision was to create a world language that was easy to learn and would unite nations.

The speakers are spread all over the world – so Esperanto is definitely a kind of “world language”. However, it does not have the status of an official language in any country. It is difficult to say how many people speak the conlang today. Estimates vary from a few hundred thousand to a few million. Most speakers are not members of the many Esperanto organisations and are therefore not registered, hence the inaccurate estimates. The most important Austrian Esperanto organisation is the Aŭstria Esperanto-Federacio (AEF).

There is also an International Esperanto Youth:

The Tutmonda Esperantista Junulara Organizo – TEJO unites Esperanto youth organisations from about 40 countries.

Esperantists often came from the international labour and peace movement. They were repeatedly victims of persecution under authoritarian regimes. National Socialists ostracized them, as did Stalin in the USSR. They were a thorn in the side of State Security because of the cosmopolitan character of the language. After all, some Western foreign radio stations were broadcasting information in Esperanto at the time.

Even today some international radio stations, such as Radio Vatican and Radio China International, broadcast programmes in Esperanto. Besides the offerings of these state-run media, there are a number of smaller publications from different countries, online magazines and portals, blogs, podcasts – even Wikipedia is available in Esperanto.

“Railwayman’s English”

“After the Second World War, many railway workers learned Esperanto because they received a bonus when they learned a language,” says Uwe Stecher, one of the advanced speakers in the group and a member of the AEF. Admittedly, many did not miss out on this opportunity since it was easy to learn.

The language was also popular among railwaymen in other countries and there were numerous railway worker’s Esperanto associations. Until 2009 Austria had the “Aŭstria Fervojista Esperanto-Federacio”, in which the speakers were organised. Jokingly, the conlang was often referred to as “Railwayman’s English”.

In the meantime, “real” English has become established as the lingua franca in many parts of the world. So why learn Esperanto today? “It is a language on equal terms”, says Petr, the Slovakian guest, and gives an example: “When an Irishman, a Finn and an Italian sit together and you speak English, the Irishman has a clear advantage. With Esperanto, on the other hand, nobody is preferred or disadvantaged”.

Uwe Stecher, Esperantist

“If someone learns Italian, Turkish or any other language, you don’t ask: ‘Why are you learning this language?

Uwe wonders about the question: “If someone learns Italian, Turkish or any other language, you don’t ask: ‘Why are you learning this particular language? It’s a hobby, it’s fun,” explains the Esperantist, who also regularly attends Esperanto congresses and is well connected in the community. There he has already met many nice people from all over the world, he claims. “It’s an enrichment,” he says, and reason enough to be interested in Esperanto.

Welcome to Esperantujo

For die-hard Esperantists, Esperanto is not only a language but also an attitude. They hold high the culture that has developed around the language over the years. This community of speakers and their culture, as well as the places and institutions where the language is used, is called Esperantujo, which literally means “Esperanto Land”. So the term is used “as if it were a country.”

The fascination for Esperanto has various reasons, and Esperantists are certain that this fascination will live on: “If every Esperantist takes at least one person with him to ‘Esperanto Land’, then Esperanto will definitely never die out,” Franziska is convinced. After all, the word Esperanto comes from hope – and hope, as we know, dies last.

Published on 14 April 2017 on fm4.orf.at

and aired on FM4 Connected